Joseph Wong has accomplished many things in his young 90 years. He is a United States Marine Corps Korean War veteran, a successful businessman, a former Las Vegas casino executive and a Hollywood film and TV extra, and has served decades as a Los Angeles Sheriff’s reserve deputy. But he holds a special place in his heart for the LAPD Reserve Corps, where he served from 1960 to 1966.

Joseph Wong has accomplished many things in his young 90 years. He is a United States Marine Corps Korean War veteran, a successful businessman, a former Las Vegas casino executive and a Hollywood film and TV extra, and has served decades as a Los Angeles Sheriff’s reserve deputy. But he holds a special place in his heart for the LAPD Reserve Corps, where he served from 1960 to 1966.

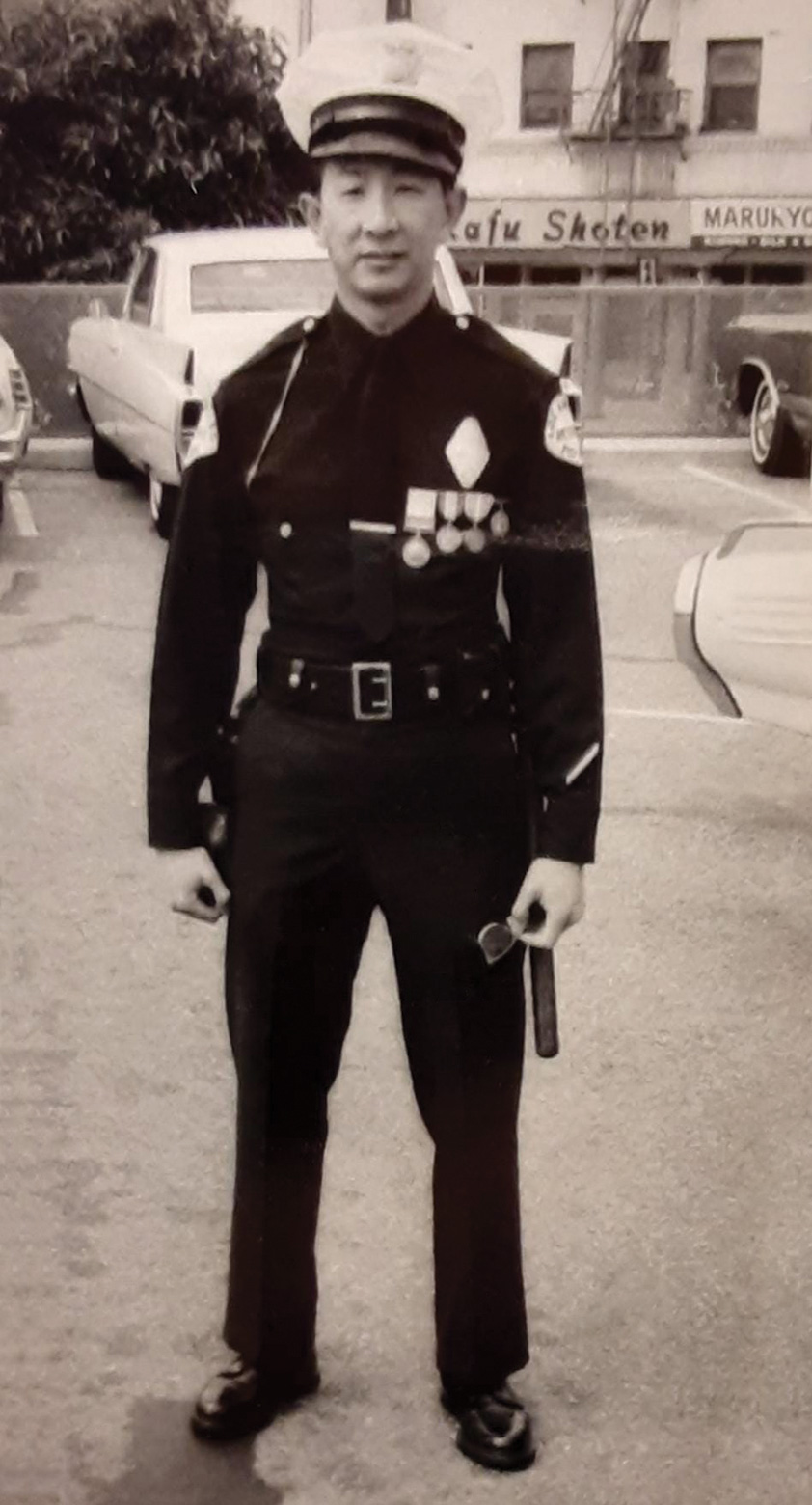

“I was a white hatter,” Wong says, referring to the distinctive uniform worn by reserve officers in the 1950s and 1960s — white cover, reserve shoulder patches, the “diamond” badges.

This year, on May 7, Wong attended the Reserve Officer of the Year gala and sat next to Chief of Police Michel Moore and the chief’s wife, Cindy.

Mel Kennedy, who has been researching the history of the reserve program, and this author had lunch with Wong at the Elysian Park Academy Cafe. Over hamburgers and fries, he told us some amazing stories.

“I knew I wanted to be in law enforcement,” Wong shared. “As Marines, we gravitated toward the camaraderie, the discipline, the spit and polish …” Already a successful businessman in Chinatown, he opted to become a reserve officer. It is a story like so many. “All they gave you were the badge, hat piece, four P-buttons and the brass gamewell box key,” he recalled. “Boy, I wish I had been able to keep that key!”

“We had to buy or somehow acquire everything else — the 6-inch .38 Smith and Wesson, the 158-grain lead ammunition, cuffs, baton, sap, whistle,” he said. At the Academy Cafe, he took his old Sam Browne out of a bag, which he had acquired from Western Costume Company, founded in 1912. Some of Wong’s fellow reserve officers got plum security work in Hollywood to help them pay for and acquire equipment for the Corps.

The 1950s “White Hat” Era

“When I joined, I didn’t know what had happened before,” Wong said. In 1960, the LAPD reserve program was a shell of what it had been, before it would be revamped in 1967. Then-Chief of Police William Parker was not a fan of reserves. “He never came to any of our events or inspections,” Wong notes. The program hit bottom in 1950, following an officer-involved shooting in which a reserve officer, following the tactics of the time, faced possible manslaughter charges. There was a firestorm in the city. Typical of the criticism was the following comment published in a letter to the editor of the Los Angeles Times, in the vernacular of the mid-20th century, dated October 12, 1950: “What kind of man would join such an outfit as the police reserve? Nobody but a frustrated smart-aleck, a jittery pistol-brave nincompoop.”

Parker used the vitriol of the moment to lobby for an increase in the LAPD budget, having ordered reserves out the field. The Police Commission subsequently removed reserve officers from law enforcement duties. Thus the “white hat” period began, in which reserve officers were relegated to an auxiliary-type status. Having been thrown under the bus, thousands of reserves resigned in protest. By the time Wong joined, there were fewer than 100 reserves left.

The reserve officer in the shooting was never charged. A full-time officer had recently been involved in a similar incident, and the cases were quietly closed.

Commendations and “Atta-Boys”

Reserve Officer Wong received many commendations and “atta-boys,” going above and beyond within the confines of the time. In November 1962, you could turn the dial on your AM car radio all the way to the left and listen to the LAPD frequency. He was driving home from a shift when he heard an assistance call. He responded, and for a while was the only uniformed presence on scene. (“We didn’t have lockers,” he noted. “We had to change at home, so I was still in uniform.”)

Officer Wong worked alongside more than 40 other reserve officers at the Police Emergency Control Center during the Watts riots in 1965. “It’s the only time I drove a black and white,” he says, as the Department managed resources and equipment back and forth. The commendation dated August 26, 1965, reads in part: “All of these Reserve Officers performed their assigned tasks in an effective professional manner. They rendered their services without complaint and with a dedication that was extraordinary and reflected great credit upon their devotion to public service. Many of them worked long and tedious hours under pressure, in addition to reporting to their regular employment in civilian life.” The commendation was approved by Deputy Chief Roger Murdock, who would later serve as interim chief of police in 1969. He had been one of the contenders for the top job in 1950, along with Parker and Thad Brown.

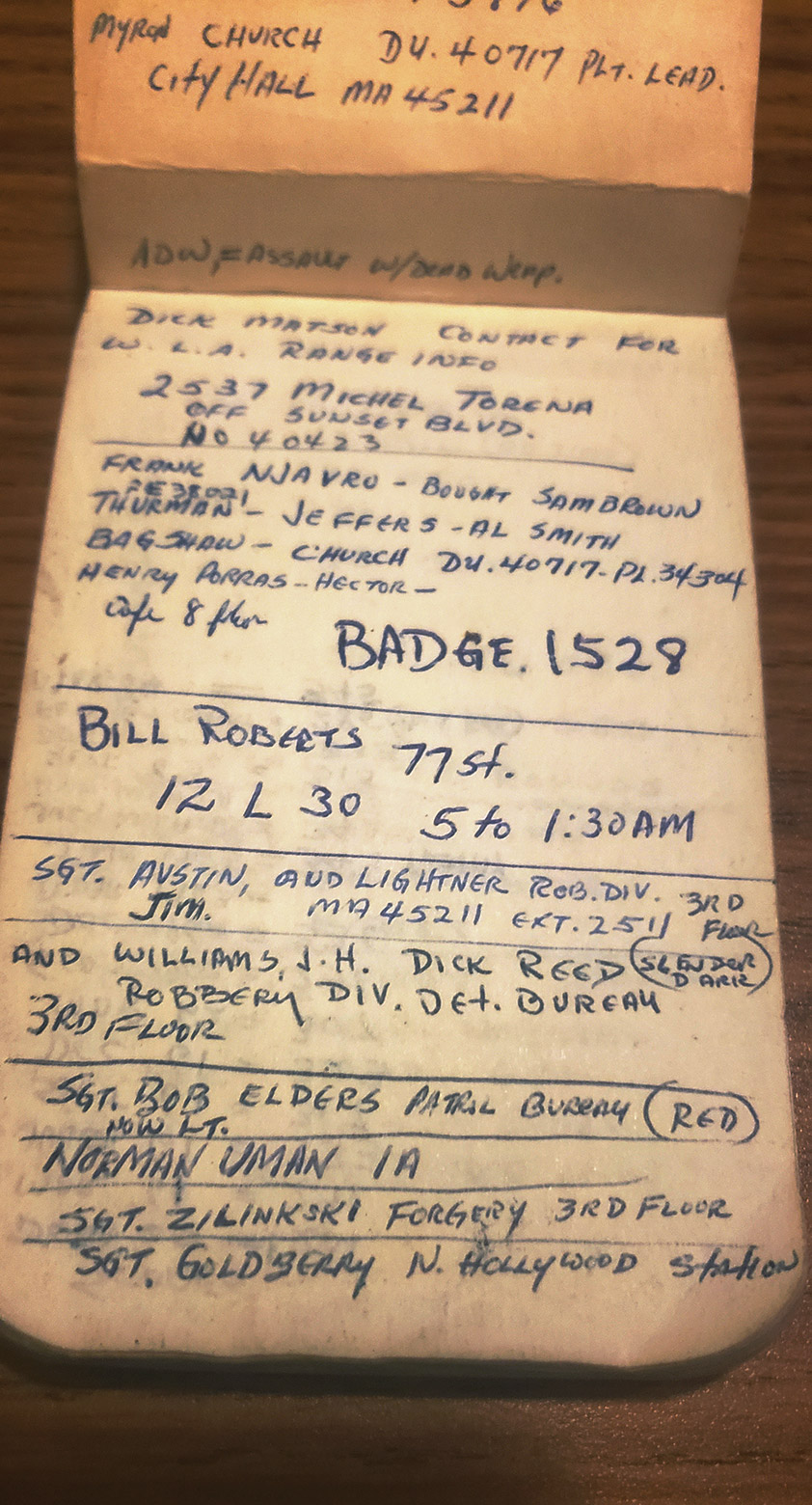

Wong showed us one of his field officer’s notebooks. It’s a time capsule, circa early 1960s, meticulously written, with perfect penmanship.

Moving on From LAPD

Moving on From LAPD

But Wong was unhappy with the Department’s limits on the Corps that prevented him from doing more. In 1966, he left LAPD and joined Alhambra P.D., where he was able to work Patrol. Shortly thereafter, Parker died, and in 1967 the reserve program was revamped, with an emphasis on field law enforcement and line reserve officers. But by then, Wong had moved on, lateraling over in 1972 to the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department.

The LASD Reserve News publication (Summer 2016) reported on his retirement from the agency: “Joe began his LASD career at the old Malibu Station on Pacific Coast Highway. After three years of patrol, he transferred to Metropolitan company … Joe worked transportation, jails at the old Hall of Justice and helped on a few homicide cases that involved Chinese victims or suspects. It was working these homicide cases that he got the ‘bug’ and asked to be transferred to the homicide reserve company. He was partnered with ‘Louie the Hat’ for 20 years. … Reserve Captain Wong retired after 56 years with the Sheriff’s Department.”

He considers former Sheriff Lee Baca a good friend and visits him regularly.

Still waters run deep, as the saying goes: In the U.S. Marines, Wong retired as a captain in the Reserves. As a merchant in Chinatown, he retired at 44 years old. Through it all, he had bit parts in hundreds of movies and TV shows. His first film was with Robert Mitchum in One Minute to Zero (1952), produced by Howard Hughes. He was in countless TV series, including Hawaii Five-O and Bonanza. “Whenever they needed an Asian, I was hired … I was the hot dog vendor in Blade Runner. … In one film, I shot Nat King Cole; you get extra money for that,” he quipped. “I get checks for a five-cent royalty, mailed with a 58-cent first-class stamp!”

After he sold his business in Chinatown, he began a new 20-year career as an executive for Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, recruiting high rollers, aka whales, from Asia. His laminated business card reads: “Joseph K. Wong, Assistant Vice President, Caesars World International.”

We asked Wong what it was about LAPD, considering all of his accomplishments, that stays so strongly in his heart. He said that it’s the same as for all who’ve had the calling: the dream to earn and wear that badge. Same as with the Marines, he said, “The LAPD allowed me to follow my childhood dream to wear a white hat and be a good guy — like the Lone Ranger!”