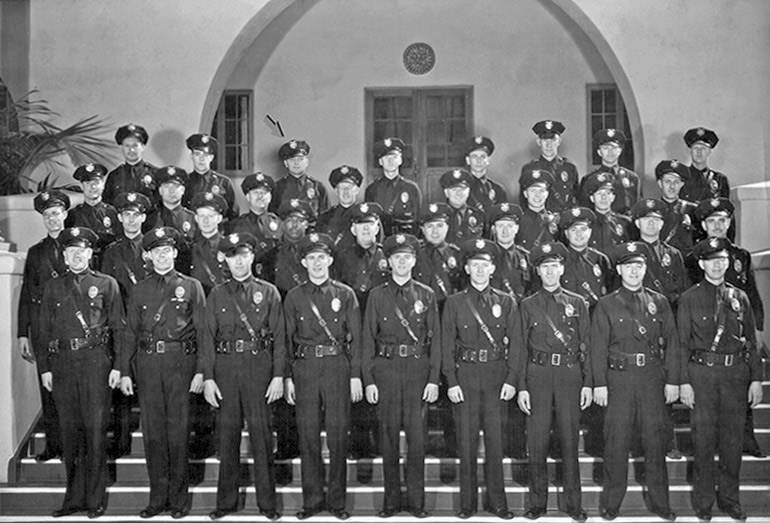

Academy class photo: Policeman Huseman is in the back row, third from left.

RESERVE CORPS LEARNS OF ANOTHER HERO:

POLICEMAN NORBERT JOHN HUSEMAN EOW DECEMBER 31,1945

After the Spring 2012 issue of The Rotator went to press, featuring the story of Reserve Policeman George Booker Mogle, we received a phone call.

The call came from Joe Cruz, a retired LAPD police officer. Joe had read the story (reprinted in the Thin Blue Line) and wanted to tell us about Chuck Huseman, who lived next door to him in Bullhead City, Arizona. Chuck had told Joe about his father, Norbert John Huseman, a Los Angeles policeman (Serial #E7425). On the night of December 22, 1945, when Chuck was about 10 years old, he said goodbye to his father, who was leaving for his patrol shift at Newton Division. That evening, his father was shot. He died nine days later on New Year’s Eve.

It has long been discussed whether there was, in fact, a third LAPD reserve officer killed in the line of duty. That has been the rumor, a legend that has persisted for many years. If you asked old timers, they would say: “Yes, I heard that. I wonder who it was.”

This may be him, although we may eventually find others. As we have only recently learned, there is a rich history of reserve officers in the LAPD preceding the official Reserve Corps — a largely forgotten history, that is now just beginning to be rediscovered. It is a history of police officers by other names — reserve, auxiliary and emergency — who served in the LAPD prior to 1947, particularly during World War II. One of these officers, it turns out, was wartime emergency Policeman Huseman, who was smack dab in the process of transitioning into full-time. He was scheduled to take the exam in January when he was killed in the line of duty.

After hearing from Joe Cruz, The Rotator began its research, an investigation not unlike the one we had just conducted on Policeman Mogle. What we discovered, once again, was a family forever affected by their loss, with memories and old photographs; and of grandchildren and others who posted on memorial pages like the Officer Down Memorial Page at odmp.org:

“To the grandfather that I still have yet to meet, you are an inspiration that will live forever through family and friends who will always love you.”

Miki Daw (Harrington), Granddaughter – January 17, 2007

“Just wanted to let you know we all still love you very much and have never forgotten you.”

Peggy Harrington (Huseman), Daughter – January 16, 2007

“You are our HERO Uncle Bert. Your thirteen grandchildren and twenty-five+ great grandchildren know about you and love you. Your brothers and sisters are all with you now so I know you are safe and warm. Each New Year’s Eve, I pause a moment to remember you. You will always be remembered and loved.”

Carolyn Ann Huseman, Niece – July 28, 2006

Carolyn is the family historian who has so far been able to trace the family history back to the 17th century in Westphalia, Germany. Family legend has it that Bernard Herman Huseman, Bert’s grandfather, stowed away aboard a ship bound for America in 1866, escaping Bismarck’s Prussia.

Norbert John Huseman was born May 6, 1912 in Nazareth, Texas, the third of eight children born to Charles Joseph Huseman and Mary Margaret Kehl. Nazareth is a farming community in the Texas panhandle, about 30 miles south of Amarillo. The family planted crops, raised cattle and sheep, and lent a hand to others when needed. They helped construct the Holy Family Catholic Parish and donated a part of their land for the one-room schoolhouse.

The Depression hit the Husemans hard, as it did many American families. And the drought — the “Dust Bowl” — hit the farmers harshly. As John Steinbeck wrote, “The last rains came gently, and they did not cut the scarred earth.” The Husemans lost their farm in the early 1930s. They packed up their belongings and moved further east, to the Mississippi town of Natchez, and Charles found work in a sawmill.

Young Bert had to go to Denver, Colorado to find work, where he met Esther Amelia Micheli. He brought her home to his family and they married in 1936. Four years later, his father died of a massive heart attack and by 1943 most of the family had decided to move west to California — to Los Angeles. The exception was Bert’s brother, Tony, who stayed and became a police officer with the Natchez Police Department.

In Los Angeles, Bert worked at Firestone Tire and Rubber Company and at a machine shop near his home. But he had a higher calling. Wartime Los Angeles generated 17 percent of the total war production. It also contributed — as all American communities did — many of its able-bodied men. World War II had drastically reduced the force of the LAPD, as many officers went off to war. It was in this environment that Norbert Huseman, now with four young children to look after, completed the Academy and was appointed a wartime emergency Los Angeles policeman on September 26, 1944.

Chuck remembers that when his father joined the Department, he sold his car — in part to pay for his uniform and the equipment he needed. But he also bought each of his kids a new bike from the proceeds.

“We lived around the corner of Temple Street and Roselake Avenue in Los Angeles, and he’d sometimes catch a bus downtown to the (Newton) station,” Chuck says. “Other times he’d ride with a friend of ours who lived upstairs, and that day my dad rode with him. I watched him go down Roselake all the way to Beverly Blvd and take a left. I watched him until he went out of sight.”

It is a memory that has never faded — still as vivid for the son as it was the day it happened, almost 70 years ago.

“To this day it’s done something to me,” Chuck says. “Whenever I say goodbye to one of my family members, or to somebody who is real close to me, I won’t watch them drive off, and I won’t say goodbye. I just tell them that I will see them later.”

Newspaper photograph: Policeman Huseman being administered last rites at Georgia Street Receiving Hospital

A fateful day

It was Saturday, December 22, 1945, nearly Christmas. General Patton was to be laid to rest in Luxembourg, Germany on Monday, with 6,000 of his Third Army troops who had fallen the year before during the Battle of the Bulge. In other news on that fateful day (as documented by The Charlotte News in an online history journal project):

- All ships in the Pacific were warned against floating mines, dumped in the closing days of the war by the Japanese.

- The Christmas menu was provided for American soldiers in Japan, including 1.5 million pounds of dressed turkey.

- A cold weekend was predicted for the country, in continuance of the cold weather trend of the previous week. (It would dip to 47 degrees in Los Angeles that night.)

- In Los Angeles, Santa Claus dropped dead, or at least an impersonator of him, as he handed out gifts at a Christmas party.

And on that day, Los Angeles Policeman Huseman, working a radio car in Newton Division, responded to a disturbance call reported as two men fighting over a baby carriage at 2322 ½ Enterprise Street. As Chuck relates, his father was working with a new officer that night. According to the tactics of the time, the passenger officer was supposed to exit the patrol car and make first contact. But because his partner was new, Huseman said he would make the contact.

He approached the location on foot and was met by a man standing outside. The door to the location was ajar; he shined his flashlight and ordered whoever was inside to come out. At that moment, a suspect later identified as Ernest Carruthers began shooting from inside. Officer Huseman was critically wounded and fell to the ground. Detectives Louis Knapp and Daniel Fredburg responded to the scene. As a crime beat article described, a gunfight ensued: “Eighteen shots were exchanged…before Carruthers surrendered.” The detectives were injured as well, although with less serious wounds.

It was 1 or 2 o’ clock in the morning when Bert’s fellow police officers came knocking on the Huseman door at 2214 Temple Street. He had been taken to Georgia Street Receiving Hospital. He had been shot in the stomach, with exit wounds in the back and on the left side, and was — as the newspapers said — “fighting for his life.” He held on throughout the holidays for a total of nine days.

Chuck remembers his mom and uncle coming home from the hospital at about 11 p.m. on that ninth day, New Year’s Eve. He asked his mother how dad was doing.

“He’s gone,” his mother replied.

“Policeman Dies of Gunshot,” said a newspaper headline, continuing: “Police Department flags ordered at half staff today.” Policeman Huseman became the first Newton Division officer to die in the line of duty. (Police Officer Ricardo Lizarraga would become the second Newton Area officer to fall, in 2004.)

LAPD officers came out in force for the funeral. “I never saw so many police cars in my life!” Chuck remembers. His father was buried at the Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Los Angeles.

“He loved the job,” Chuck says of his father, who was planning to go full-time with the LAPD. But at the time of his death Policeman Huseman was still classified as a “war emergency officer” — having not yet processed in as a regular. Under the rules of the day he was not eligible for the police relief fund and his family was systematically denied financial assistance. As the Los Angeles Times wrote at the time, this resulted in a groundswell of support as “brother police officers rallied to the aid of the family,” starting a collection to help his widow Esther and children. The family also was able to qualify for some state compensation.

The suspect Carruthers was charged with three counts of “assault to commit murder.” Chuck remembers going to court one day during the trial and seeing the door from the suspect’s location — presented as evidence — riddled with bullet holes. Carruthers was convicted (of what specifically is unknown) and sentenced to prison, but released after serving only about eight years. No one in the Huseman family today can say why.

“I don’t know why. It seemed so strange to me,” his son says.

Chuck had to finish growing up without his father but had an Uncle Teddy and the close-knit Huseman family looking over him. His grandmother, Mary — whom Carolyn calls “the rock, the foundation of the family” — stayed with Esther and the kids at the house on Temple Street until she died in 1947. (Esther remarried and passed away in 1983.)

In the early 1990s during a meeting at the Academy, it was incidentally mentioned that no Newton Division officer had ever fallen in the line of duty. Someone in the audience stood up and begged to differ; the person didn’t know the details but was certain there had been a fallen officer. As a Times article then reported, Detective Gail Ryan (now retired) “put her sleuthing skills to work and verified that a Newton officer… had never been officially honored by the Department.” She tracked down Chuck Huseman, who had just moved to Bullhead City, and a service — complete with vintage LAPD uniforms from the 1940s — was arranged. Chief of Police Daryl Gates attended to honor Policeman Huseman.

LAPRF President Mel Kennedy, who has been researching the history of the Corps, says reserve law enforcement “has played a far more integral role in protecting the citizens of Los Angeles than has ever been acknowledged.” He has recently traced newspaper accounts that go back to the 1860s. At one point, the City of Los Angeles had authorized the Chief of Police to deputize up to 11,000 officers (up from an original decree of 400). During World War II, there were over 2,000 reserves. “We must find their stories,” says Kennedy. “We must honor these officers and their families. We must not neglect the record of their service, or forget their legacy. This is the least that we owe them.”

The history of war emergency police officers like Policeman Huseman still needs to be researched — their position in the Department and relationship to what would become the Reserve Corps more fully understood. But there is no doubt of the legacy these brave heroes have left behind. They were there when the city needed them most, reinforcing the LAPD when the country was at war. Policeman Huseman is an example of what the LAPD Reserve Corps is all about.

Yet it is the families that in the end must endure the sacrifice. Time and again, in researching this story, we heard about the closeness of the Huseman family; their resilience and ability to stay together; and their long family tree, which now prominently includes a lost LAPD hero, Norbert John Huseman.

His son concludes: “He was a great dad. He was like Superman to me. I’m sorry my kids never got to meet him.” We very much agree.