Review of A Sense of Humor: Reflections of a Life, by James Carl Lombardi with Lisa Lombardi O’Reilly, 2019, 278 pages, $18, available on Amazon.

At The Rotator, we were perplexed by the conundrum of trying to decide whether to go with a standard book review of James Lombardi’s new autobiography, A Sense of Humor, or publish an excerpt of the book by Jim and his daughter Lisa to let his story speak for itself. As you can see, we wisely chose the latter: a chapter, “Skippy’s Golden Gopher,” about the OIS. But in our decision, an important part would be missing — the rhythm, the beat, the tempo and the sway of Lombardi’s Restaurant.

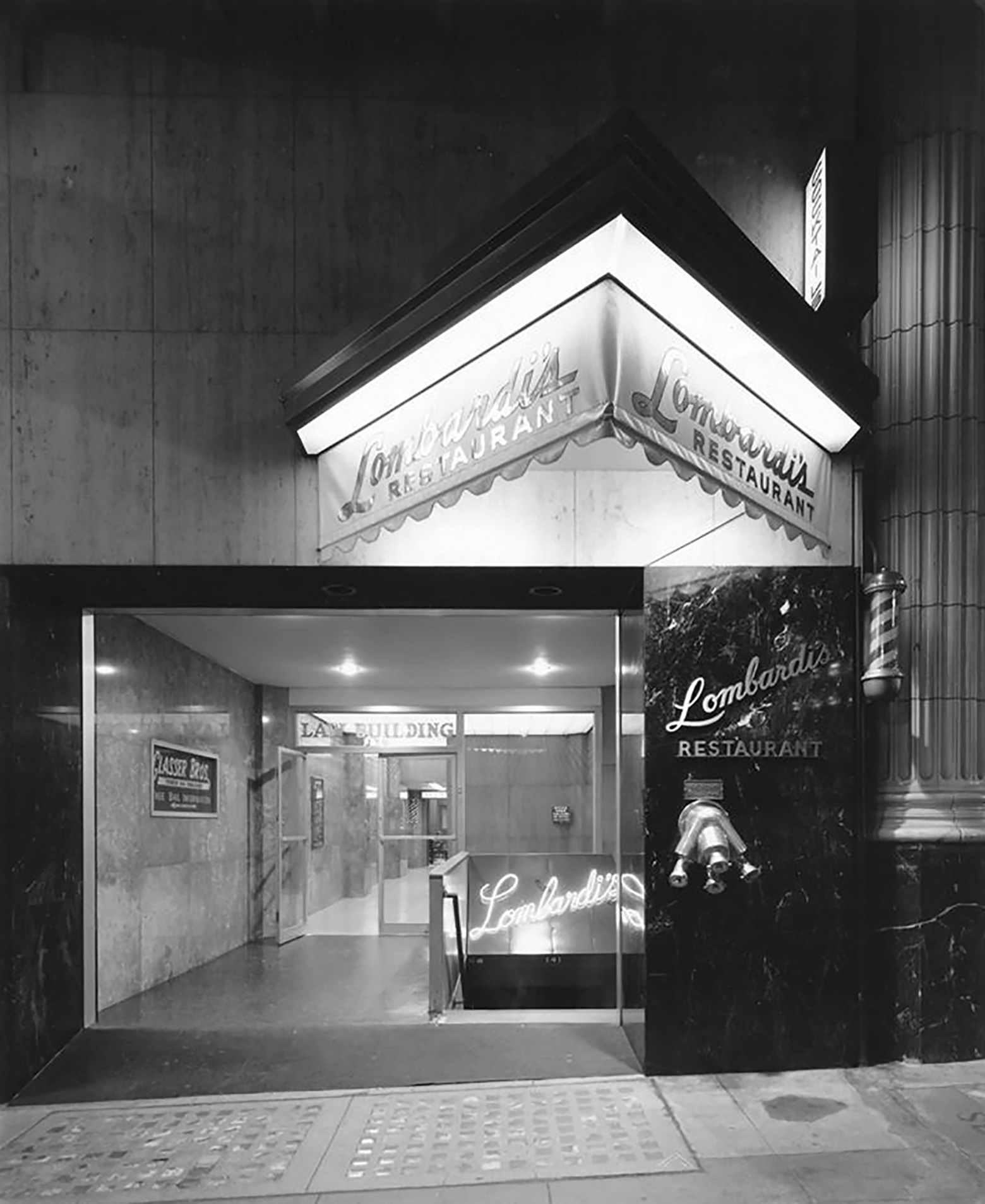

In the early 1960s, James Lombardi was thinking about joining the police department full-time. But instead, for the moment, his father had a plan for him: to run a restaurant in the Law Building on Broadway, which James Sr. owned. The restaurant was eventually moved to Seventh and Flower, after the Law Building had been condemned. Seventh and Flower was the Roosevelt Building — an Italian Renaissance Revival-style edifice built in 1925 that still stands today, with high-end lofts and one of the busiest stations on the Metro Red Line. In the autobiography, Lombardi regrets that his family didn’t buy the building at the time. The Rotator did some research: Today, the Roosevelt has 222 apartment/lofts. A one-bedroom/one-bath (728 square feet) is between $2,575 and $4,541 per month.

The marquee of Lombardi’s Restaurant when it was located at the Law Building on Broadway

Lombardi’s Restaurant became a legend of its time; the proud owners were Jim Lombardi and Charles “Chuck” Ratigan Jr. In “Downtown L.A.’s Liveliest Spot,” Patterson’s called it “one of the most unique restaurant operations this side of San Francisco … Lombardi’s turned into the swingingest dance floor in the City of Los Angeles.”

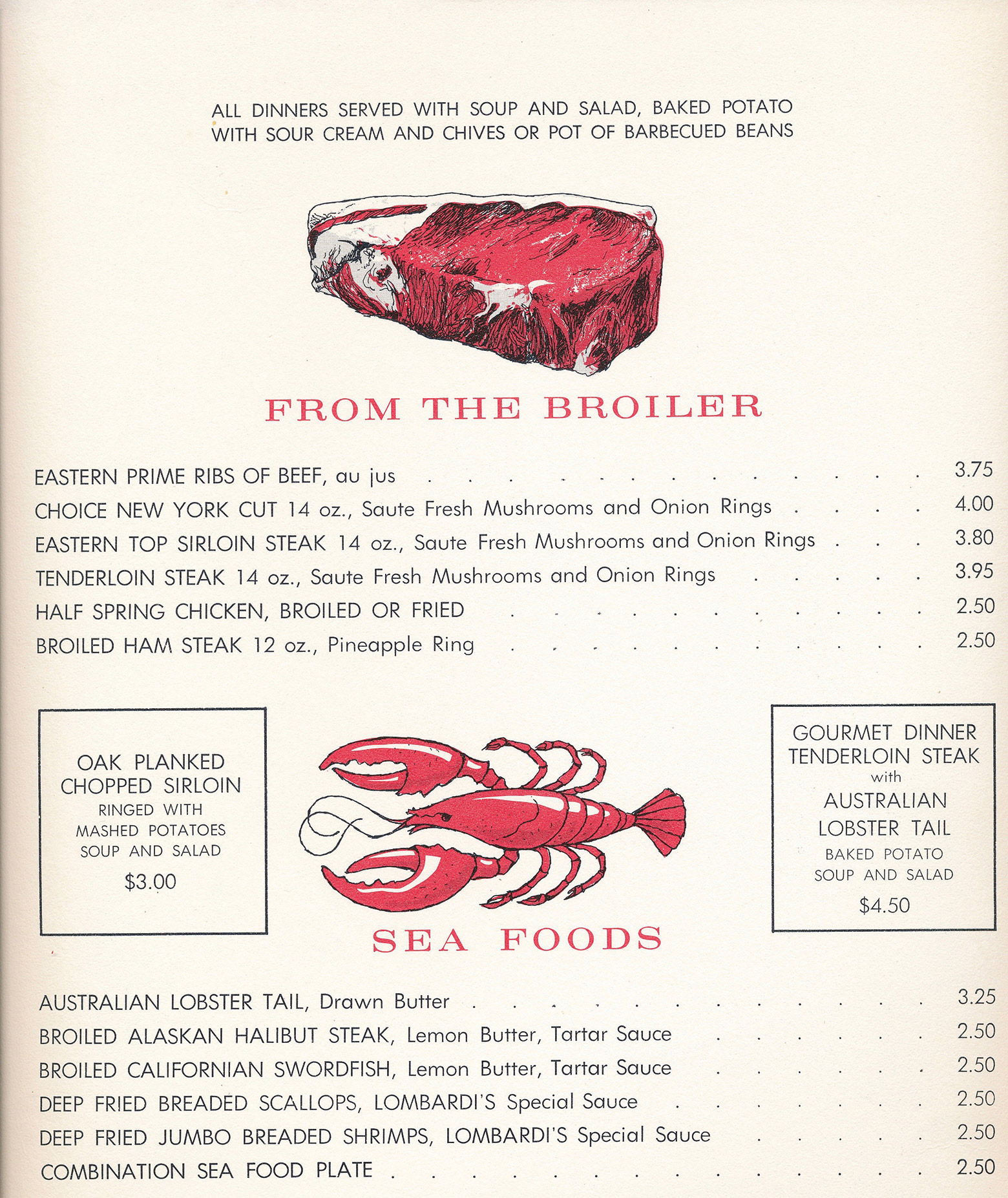

The steaks came from his Grampa Lombardi’s cousin in Denver, who also had supplied meat to the Eisenhower White House. Lombardi says, “I was buying New York strips and prime rib from him. You don’t see meat like that now, even in the highest places.” The menu had Eastern prime ribs of beef, au jus, for $3.75. The choice New York cut was $4. Australian lobster tail, with drawn butter, $3.25. You could wash your meal down with Peter Dawson’s, the house Scotch whisky (established in Glasgow, 1892).

“The line to get in would go around the corner,” Lombardi recalls. “We were really big at lunch, and dinner during the week after everyone got off work, and since it was downtown L.A., everybody was dressed up. We had lawyers from both sides of the aisle… Criminal defense lawyers and district attorneys.”

One person came in, saying he had heard about the restaurant all the way from England. Lombardi’s had a dress code, coat and tie for men, so he didn’t get in. Another who had trouble getting in was Hollywood gangster Mickey Cohen. “It didn’t last long. He was just a jerk and didn’t impress me,” Lombardi writes in the book. In a Winter 2012 interview, he described the episode to The Rotator:

Lombardi: When Mickey Cohen came down the steps to the head of the line, where I was seating people, I told him he’d have to go to the back of the line and that it would probably take about 20 minutes. He said [accent], “You don’t understand; I’m Mickey Cohen. You gotta let me in.” I said, “Nice to know you, Mr. Cohen, but the sign outside says Lombardi’s Restaurant, and I’m Jim Lombardi. But I’ll let you ahead of these people if you ask them for their permission.” He was so livid that he began to cry. I couldn’t believe it.

Rotator: Did you think he might want to have you “sleep with the fishes”?

Lombardi: [laughs] I’m sure he did, but my main concern was his two bodyguards.

A page from the Lombardi’s menu

Jim is a gentleman in his bio, and one gets the sense he is being discreet in the stories. Yet he added a few. A character named Jack Hildreth “did criminal defense work and he was a drinker. He was such a good customer, they gave him a phone at the end of the bar.” One day, he had to be back in court at 2:00 to defend the nephew of Jack Dragna, a hitman for the mafia dubbed the “Capone of Los Angeles.” “One-thirty comes around,” Lombardi recalls, “and he’s in the cups, so he calls into the court clerk and said, ‘Is the judge going in on time? Yeah? Is Dragna there, have you seen him?’ She told him he was there waiting for him and he said, ‘Well see if you can just plead him guilty.’ And that’s what happened.”

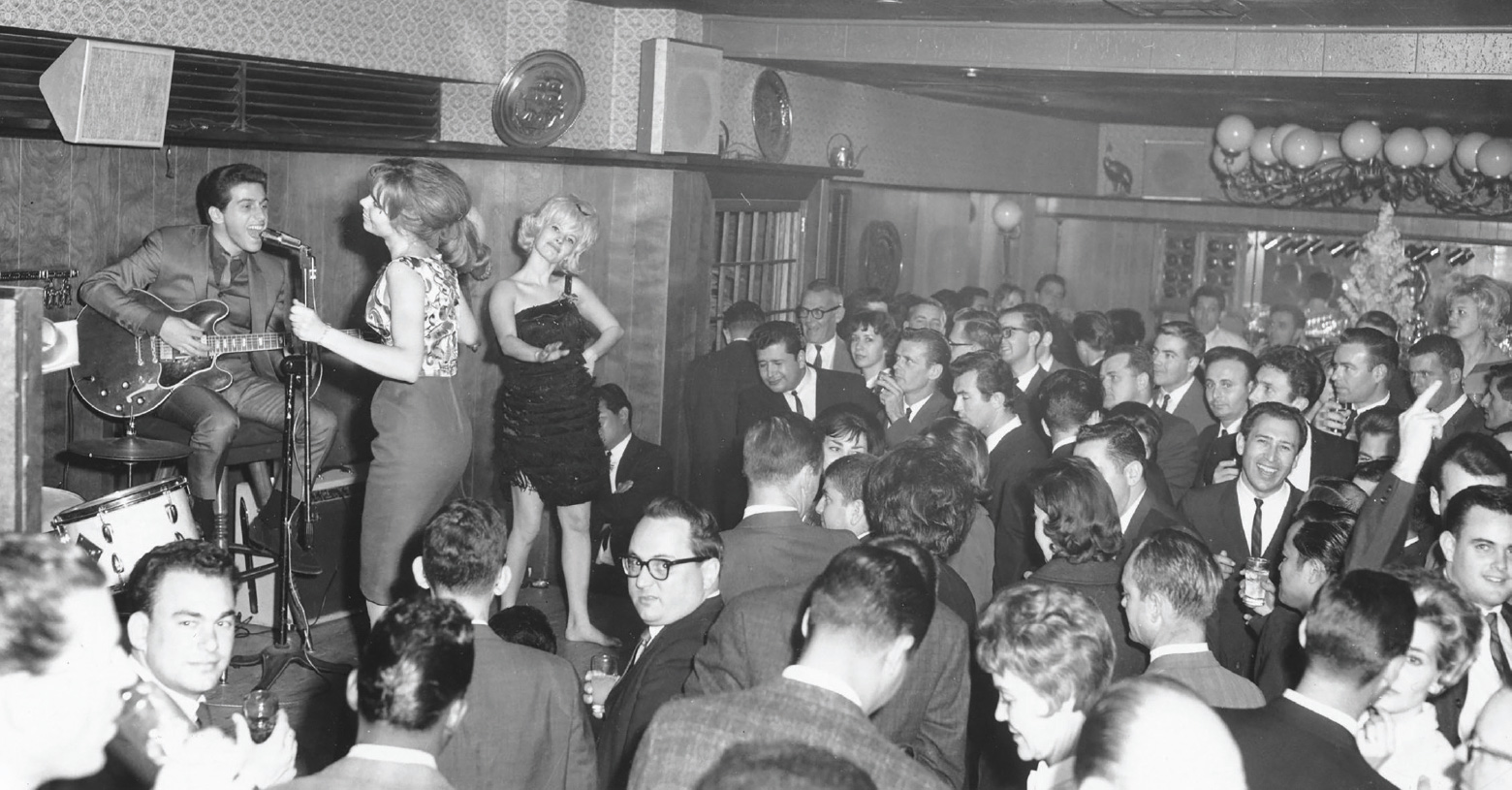

The “swingingest” times were when some booths were replaced by a stage. Among those who took the stage was Johnny Rivers (known for “Memphis Tennessee,” “Secret Agent Man,” “Baby I Need Your Lovin’” and “Summer Rain”).

One more story: “The Green Bay Packers used to come to town to play and they’d come to Lombardi’s for the girls.” They had a 10 p.m. curfew because of game day, but they’d break that, getting back at two in the morning. They’d say “they were with Lombardi, so it sounded like they were with the coach [Vince Lombardi].”

Some of his customers were LAPD cops, so the idea of joining the police department came back up. They told him about a new line reserve program, with an emphasis on patrol and field work. Lombardi said, “I really went into it with the thought that I was going to go full-time police.” He went to work at Central Division.

Jim sold the restaurant around 1970. “It was just so much work after 10 or 11 years, and my kids were getting up in age in school and Bev and I were looking towards our future.”

Finally, for a story about a guy named Lenny Jones, who had stiffed the restaurant for 350 bucks, became “white as a sheet” and started shaking when he saw the shotguns, you’ll have to buy the book. It’s a fantastic read, the journey of the man who made his indelible mark on reserve law enforcement in California, on the history of the LAPD and on all of us — and who also, as if all that had not been enough, once had the swingingest place in town.

Johnny Rivers on stage at Lombardi’s. “The girl on the stage in the fringe dress worked in the area and she’d come at night,” Lombardi says. “She was always by herself and never left with anybody.”